Gavin Black is director of the Princeton Early Keyboard Center, Inc., Princeton, New Jersey (pekc.org).

The harpsichord: an introduction, part 3—Glossary

For the past several columns, I have been writing an introduction to the harpsichord. This month, I aim to provide a concise glossary of terms, which in turn will make it easier to be clear as we move forward. For thoroughness I include some terms that I have discussed already. I also include some that seem intuitively obvious, again for thoroughness and easy reference.

1) Large, solid components

Case—the outside of the instrument, what we can see from across the room. It must be strong enough to contain everything inside, provide stability, yet still be resonant.

Bentside—any side of the case that is curved, usually a long piece at the player’s right. Some bentsides have one curve, some have two (in the manner of a grand piano).

Cheek—the piece of the case that starts on the player’s right nearest to the player. It is straight and connects to the bentside, if there is one.

Tail—the tip of the instrument, near the ends of the lowest strings.

Spine—the side of the case to the player’s left, running next to the lowest strings, and never curved.

Lid—the top of the case, which is hinged and can be opened. The part of the lid nearest the player is often also hinged and can be opened independently.

Prop stick or lid stick—supports the lid in its open position. Sometimes attached and hinged to the case, but usually separate.

Bottom—the underside of the harpsichord, usually solid.

Stand—the assembly of upright pieces and cross pieces on which the instrument rests. Some stands come apart for moving, others do not; some have pegs in the top that must be fitted into holes in the bottom of the instrument, others do not.

Legs—these usually screw into blocks found on the bottom, sometimes they are hinged and fold up.

Nameboard or name board—the wooden piece directly above/behind the keys, sometimes inscribed with the maker’s name, though often not.

2) Fixed components inside the case

Wrestplank or Pinblock—right behind the nameboard, the heavy wooden block that holds the tuning pins (see below).

Gap—just past the wrestplank, a rectangular space in the instrument, running perpendicular to the strings. This contains some of the components of the action described below.

Soundboard or sound board—the large wooden board past the gap and extending throughout the rest of the instrument, parallel to the floor. It is sometimes decorated, but often plain, usually varnished. It is meant to be resonant and has a large role in shaping the sound of the instrument.

Bridge—a curved piece of wood (in the shape of a low wall) glued to the soundboard, running diagonally from front right to back left. The strings rest on the bridge, and the bridge helps transmit vibrations of the strings to the soundboard.

On an instrument with only 8′ stops there is normally one bridge; a 4′ stop will have a separate (smaller) bridge; in rare instances where a 16′ stop is present, it usually has its own (larger) bridge.

Nut—mounted on the wrestplank near the gap, it looks just like a bridge. It serves to keep the strings in place, but has at most a small role in transmitting vibrations to the rest of the instrument.

Rose or rose hole—a round hole (called the rose hole) cut in the soundboard toward the bass end, which usually has some sort of decorative element (called the rose or rosette) placed in it—often, but not always, the maker’s insignia.

Hitch pin rail—a narrow railing running along the side of the instrument to the player’s right, firm and solid enough to hold the hitch pins (see below) in place. If there is a 4′ stop, the hitch pin rail pertaining to that stop is found in the middle of the soundboard.

3) Moveable components, including action parts

Strings—harpsichord strings are almost always metal, iron/steel or brass. Very low strings are rarely overwound. A set of strings, one per note, is referred to as a choir of strings.

Hitch pins—the ends of strings farthest from the player are attached to pins firmly mounted into the instrument, called hitch pins. For tuning stability there should be no give or slack in hitch pins. They should curve toward the side/back of the instrument to prevent the strings from riding up or coming off.

Hitch pin loops—a loop at one end of each string that fits over the hitch pins: it should not be able to loosen or slip even an infinitesimal amount.

Tuning pins—near the keyboards, mounted into the wrestplank, there are removable pins onto which the strings are wound, analogous to the pegs in a violin, guitar, etc. Turning them clockwise (viewed from above) increases tension on the strings and raises pitch; counterclockwise decreases tension and lowers pitch. They are turned by an external tool (see below). There are two types of pin in normal use—“antique” pins, the tops of which are narrow rectangles, and “zither pins,” the tops of which are approximate squares. The former are tapered and unthreaded. They stay in place just by their tight fit in the wrestplank. Zither pins are normally very finely threaded.

Tuning hammer/wrench/key—the device that fits over the ends of tuning pins and enables a tuner to turn those pins. The terms are used interchangeably with no distinctions among them. Those that fit antique pins cannot fit zither pins and vice versa.

Key—the same as with any keyboard instrument. The term refers either to the part of the key that we see or to the whole key, including the part behind the nameboard. Harpsichord keys are simple levers with no internal moving parts.

Keyboard—again, the same concept as with any keyboard instrument—a set of keys, one per note, arranged so as to be playable according to normal expectations. A harpsichord keyboard is often called a manual, as it is on the organ. A harpsichord with one keyboard is called a single, and an instrument with two keyboards is called a double.

Short octave—when the lowest keys play notes lower than a normal arrangement. In the most common form the apparent lowest G-sharp key plays E, the F-sharp plays D, and the E plays C. A variant called a broken octave has split keys (see below) enabling the G-sharp and F-sharp to be played as well as the lower notes.

Split keys—keys in the position of sharps/flats in which the front and back of the key move separately, playing different notes. This can be used in the broken octave (see above) or to give the player both the flat and the sharp for a given note position (e.g., C-sharp/D-flat), for tuning systems in which those are different.

Coupler—a device that allows the upper manual to play on the lower manual. On a harpsichord, a coupler is engaged or disengaged by shoving one of the keyboards in or out. (Note that this can be either keyboard.) Some couplers cause the keys of the other keyboard to move visibly up and down.

Transposing keyboard—this can refer to the keyboards of certain rare but important early Baroque doubles in which the two keyboards play at different pitches from each other. More commonly, nowadays, it refers to a keyboard or pair of keyboards that can be shifted from side to side by the distance of one or two notes, causing the keys to address different jacks, and thereby to play at different pitches. This is a twentieth-century invention and exists mainly to allow an instrument to play with both modern instruments (usually at A = 440 Hz) and certain Baroque-style instruments at A = 415 Hz.

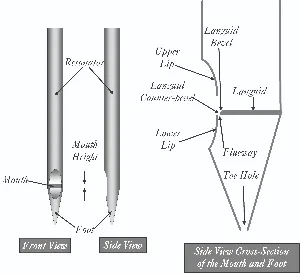

Jack—a rectangular device with several moving parts that sits on the back of a key and rises when the key is played. When a key is released, the jack comes back down by gravity. A jack contains the plectrum and the damper (see below for both) and, as part of its internal workings, a small moveable piece called the tongue, into which the plectrum is set, and a spring that enables the tongue to move back and forth properly, and thus the plectrum to pluck the strings. A row of jacks, one per string of a choir of strings, is called:

Register—That word is also used to mean the flat wooden piece roughly on the level of the soundboard, in which the jacks rest.

Jack rail—a length of wood above the jacks and the registers that keeps the jacks from flying out during play. Removable for voicing and regulation (see below).

Stop—a register of jacks playing a choir of strings, the same concept as an organ stop. A stop is turned on and off by sliding its register back and forth very slightly, moving the plectra (see below) under the strings or out from under the strings.

Plectrum or quill—a small piece of plastic or bird quill that plucks the strings. It is set into the tongue (see above), which pivots in such a way as to force the plectrum to pluck on the way up and to allow it to slip around the string silently on the way down.

Damper—a small piece of felt set into a jack in such a way that when a key is at rest, the damper sits on the string and prevents it from vibrating. When the key is played, the damper moves off the string. When the key is released, the damper settles back onto the string to stop its sound.

Buff stop—a set of felt or leather pads that can be pressed up against all the strings of a choir, changing the sound to a more muted, mellow one—somewhat closer to the sound of a lute or other hand-held plucked string instrument, or to pizzicato. The buff stop is often called a lute stop; however, this was not the traditional term in the Baroque era and is not officially correct.

Voicing—the shaping of the plectra in exact detail to give the desired strength of sound and touch. Plectra can be altered as to length, width, and thickness, all within certain limits. Any alteration of a plectrum changes the sound and touch.

Regulation—any work that makes the harpsichord function properly. This can include adjusting the exact length of jacks, angling dampers correctly, replacing worn-out springs, and much more.

Pitch or pitch level—the approximate overall placement of the pitch of the instrument. That is, whether A is around 440 Hz, or 415, 409, 392, or something else—along with the assumption that all the notes will cohere with that pitch level. Note that whereas we expect almost every piano or organ to be at approximately A = 440 Hz, harpsichords do vary significantly in their overall pitch, and in the Renaissance and Baroque periods varied so much that there was no standard pitch over the harpsichord-playing world.

Temperament—the exact pitch relationship among all notes of a harpsichord, regardless of the overall pitch. That is, given a starting note, which intervals are exactly pure, and which are a bit narrow or wide. There is an infinite variety of possible temperaments.

To be continued.